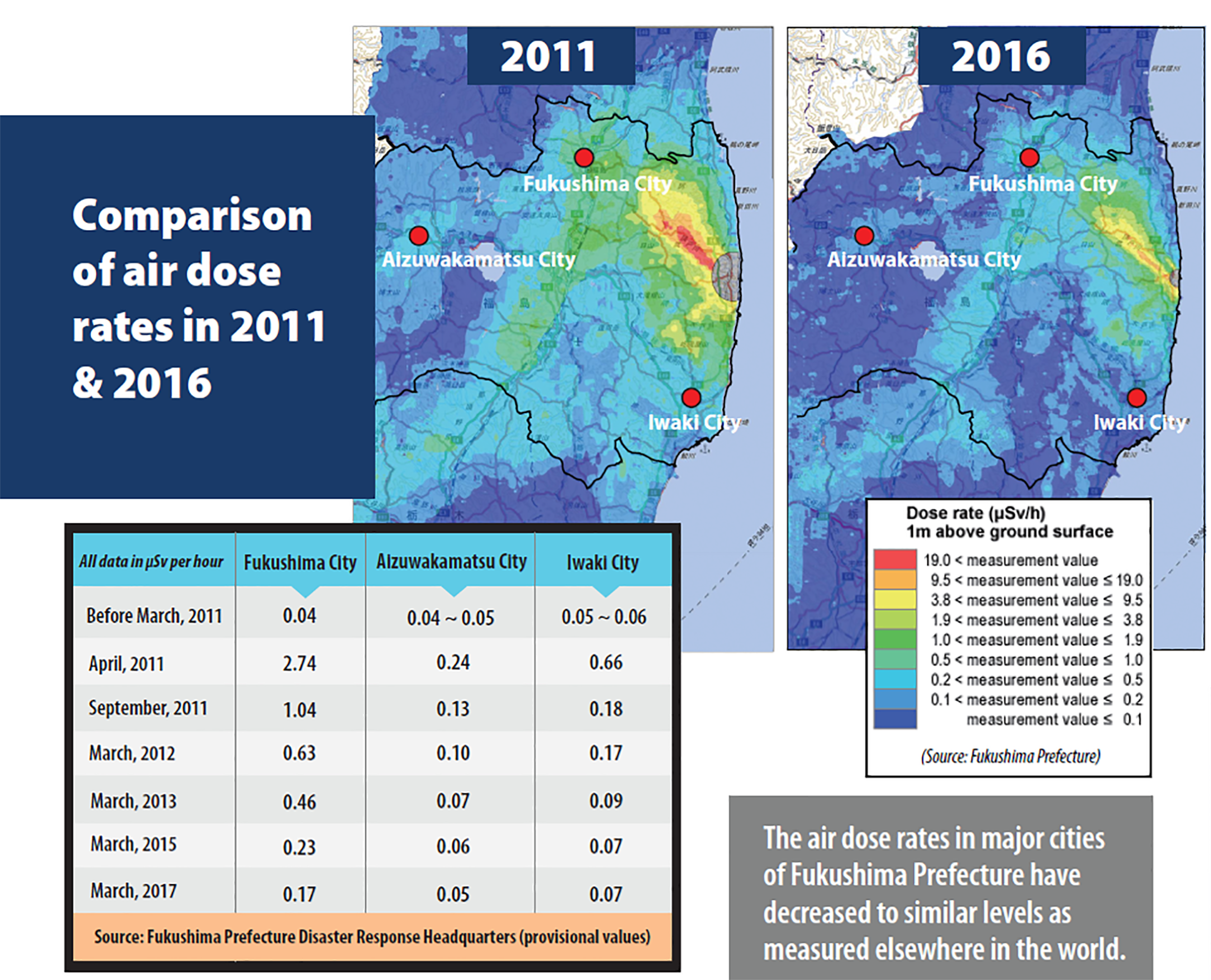

Less than an hour. That’s the time it took the earthquake-triggered tsunami of 2011 to reach Japan’s eastern shoreline. Soon after, the first tsunami hit the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, leading to an accident that forced tens of thousands of people to evacuate. Since then, the Government of Japan and the authorities of Fukushima Prefecture have made significant efforts to make much of the evacuated areas inhabitable again. A decade after the accident, what does life look like in the affected areas of Fukushima Prefecture?

“Japan’s efforts to clean up residual radioactive contamination have been enormous,” said Miroslav Pinak, Head of the IAEA’s Radiation Safety and Monitoring Section and team leader of an IAEA project to support the Fukushima Prefecture in the recovery work. “Since 2012, the IAEA has been providing assistance to the Prefecture in that and other activities, including radiation monitoring, and analyzing and communicating the results effectively. Children are now playing in school playgrounds and hikers are using the forests of Fukushima Prefecture where access was restricted following the accident, and we see this as a definite success.”

The IAEA has provided technical expertise, equipment, expert missions and guidance on recovery operations — based on international examples and the IAEA safety standards. It has been supporting Japanese authorities and scientists in three technical areas: radiation monitoring, remediation and the management of waste from decontamination activities.

Radiation monitoring is important when dealing with a nuclear or radiological emergency. Experts need to answer key questions. Has there been a release of radioactive material? If so, what types and amounts of radionuclides have been released? How can people and the environment be protected in the most effective way? To answer such questions, radiation levels in the environment need to be measured frequently during an emergency.

“During an emergency, radiation monitoring assists in determining whether protective actions, such as sheltering or evacuation, are implemented precisely where these actions are needed and when they are needed,” said Florian Baciu, Acting Head of the IAEA’s Incident and Emergency Centre.

Significant amounts of radioactive isotopes of caesium, or radiocaesium, were released into the air and deposited in the forests, soils and bodies of water of the Prefecture. With IAEA help, Japanese authorities have established long-term monitoring programmes to detect radiocaesium on land and in water, in addition to measuring radioactivity in wild animals, mushrooms and other food from the forests.

Because of natural radioactive decay, it is expected that the radiation level will gradually decrease, Pinak added. “According to the results of the long-term monitoring programme in forests, the air dose rate overall decreased by about 78% between 2011 and 2019. As time progresses, radioactivity concentrations in forests will continue to decrease and monitoring programmes will reflect that tendency.”